We often use the word “nesting” in relation to filling our homes with all the sundries meant to make it cozy, comfy, and intimate, creating the ultimate refuge from the world. People refer to a lovers' den, at times with derision or judgment, as a “love nest.” And Gaston Bachelard wrote in his seminal Poetics of Space, “Thus the dream house must possess every virtue. How ever spacious, it must also be a cottage, a dove-cote, a nest, a chrysalis. Intimacy needs the heart of a nest.”

But to actually build a nest? With beak and claw? Using spider’s webs, caterpillar cocoons, plant down, mud, found modern objects, hair, feathers and down, sticks and twigs, moss and shells? This form of construction and design might be the truest kind of architecture, ingenuity, survival, and sustainability there is.

San Francisco-based artist Sharon Beals honors this fragile architecture with her book “Nests:Fifty Nests and the Birds That Built Them,” featuring gorgeous photographs of various species’ nests, all from within the past two centuries, currently preserved in several museums throughout the United States. Her photos have been exhibited at the National Academy of Sciences, the Morris Museum, and Gensler Architects in San Francisco. Beals’ prints will BLOW YOUR MIND – they’re exquisite and magnificent, each of them so wildly different in color, construction, shape, and density, that to this day I’ve been unable to decide which nest to buy (I’ve settled on a top five list and am taking it from there). We are so stoked to talk with her (at fairly great length, so we suggest to grab a cup of tea and settle in!) about her rescue pup, Tucker, the future of our environment, and her favorite room in her house.

Lily Spindle: Can you tell our readers who you are?

Sharon Beals: Half of my life was spent in Seattle, with a veer to the east coast, and the rest here in San Francisco, though I’ve never lost my love of moss and moisture. I’ve been photographing since my twenties, doing mostly editorial work, but along the way making photographs for myself and who ever would look at them. Lately my art has taken over, with gallery shows and collectors, and I’ve begun research and the photography for a second nest book.

Hoary redpoll (Acanthis hornemanni). Collected from St. Michael, Nome County, Alaska, 1896. Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. These tiny seedeaters survive minus-80 degrees Fahrenheit Arctic temperatures by doubling their weight in down in winter and living off plants not buried under the snow. Using a pouch in their esophagus, they can store seeds to be regurgitated and eaten under shelter. They also build well-insulated nests lined with willow cotton, caribou hair, vole fur, feathers, fine grass, and in this case, even sheep’s wool.

LS: Tell us a bit about how your NESTS book came about. What's something incredibly poignant or sweet you learned about birds and their nest-building during the process of putting together this gorgeous book?

SB: The nest book evolved from a few nest photos on my studio walls. Visitors who might never pick up a pair of binos, were curious about the birds that built them. Why not try to do a book? What evolved is cross between art and science that tells the stories of the nest builders, inviting others to learn about the survival issues affecting them.

When I signed the contract to do the book, I took a deep breath and decided to do the writing too, diving into a tunnel of research, trying to parse dry data into comprehensible and engaging stories.

Fortunately, I’ve been allowed to documents the eggs and nests in five different ornithology collections: The California Academy of Sciences, Cornell’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, The Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. I can’t quite name the wonder and awe contained in cabinet drawer in a new collection, I can just try to capture it in an image.

Altamira oriole (Icterus gularis). Collected from Morazón, El Progreso, Guatemala, 2001. Relatives of blackbirds and meadowlarks, altamira orioles can be found from the Rio Grande to Nicaragua, living in year-round territories as lifelong pairs. It can take the female a month to weave a nest, which is entered from the top. In Texas, altamira orioles are considered a threatened species due to the loss of the native trees of the Rio Grande to agriculture and flood control.

So many of their stories of these feathered wonders are compelling to me, if only for their migration stories. Young songbirds, some maybe a nickel in weight, and without any parental guidance, navigate hemisphere-to-hemisphere flights of thousands of hazardous miles to spend warm winters in the same feeding grounds as their ancestors, These days, those sources of food may or may not still be there when they arrive. Come time to breed, they reverse that journey, and the face the same gamble.

But when it comes to nest building, one bird stands out for just sheer endeavor. In a month-long collaboration, A pair of Long-tailed Tits collects over three hundred pieces of moss, spiderwebs and the silk of about six hundred cocoons, pressing these into a flexible egg-shaped dome, which they insulate with 1,500 to 2,000 feathers that take twenty-eight miles of flying to collect, finally camouflaging this creation with 3,000 bits of lichen. I imagine it’s a similar feat for those tiny Bushtits we have here in California.

Cuban Emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii), Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, Collected from Andros Island, Bahamas, on January 22, 1988.

LS: What is your biggest concern about what we're doing to our planet and its creatures, both big and small? Do you think what we're doing can ever be undone?

SB: It’s hard not to immediately think of climate change as the ultimate scythe, with even the current small rise in temperatures changing habitats right before our very eyes. Locally you can look at swaths of red and dead pines, felled by drought-stress and opportunistic pine beetles no longer slowed by a cold winter. This might be fine for some birds as food sources right now, but others that use the trees for safe cover will suffer.

These warmer, shorter winters also affect other insects, changing the time they hatch. As the main food of choice for birds, 95% of which feed their young with insects, by the time the birds arrive, these important protein rich calories may have flown. And of course, whose heart doesn’t break hearing about polar bears having to swim so far from ice flows to feed that their young starve? Or the glaciers everywhere, cascading away.

Do I have hope that we can reverse that? Of course we can look at the surge in solar, and bankrupt coal companies, and so many people all over the planet getting loud during the international climate conference. But hope is hard to manage when I look at crawling, SUV-laden freeways. Or recycling bins full of Amazon boxes, all of which come with a carbon cost. Or sometimes even looking at Facebook with everyone’s vacation pictures. My brain is like this carbon calculator, and it’s not a lot of fun being me, knowing that one airplane flight has a footprint that kills even the greenest persons energy conservation. Note to self: find an honest carbon offset vendor, not the little drib airlines offer.

“Use less stuff (I love that Lily Spindle is all about reuse). Know where anything you buy and what it’s made of comes from. Eschew those palm oil-laden snacks and think of orangutans, carry your own drink cup and bottle. Give up your scented laundry and body products, and just put a little good cologne behind your ears (what we are doing to water affects birds, mammals and fish downstream). Walk, bike, bus, train, and teleconference in some fun way. Go solar if you can, and travel electric. Buy “bird friendly” coffee. Plant your locally native plants to feed the insects that feed the birds, and join friends and neighbors to restore some land, or a vacant lot. And donate to or vote for anyone who is noisier than you about climate changing laws. ”

LS: Your little rescue pup, Tucker, is one adorable, vociferous hiking companion. Can you tell us the story of how this little heartbeat at your feet came to be yours?

SB: Ahh, Tucker! My significant other. My last good girl Ellie had left the planet, so a friend who works at Animal Care and Control asked if I would take this five week old pup in for a weekend. Of course this tender snuffler stayed for a week, and then another and when he was old enough, I signed his adoption papers with only the slightest hesitation. I’ve only rescued older dogs, so a pup was new territory. Of course one of his buddies taught him to bark, but he breaks my heart with his good-to-the-world nature. He and I are both lucky he’s so easy to love; he’s charmed the hearts of a small village of friends who love to take him in when work tears me away from him.

LS: Are you a morning person or a night owl?

SB: I am both, I can swing out of bed at five for early light, or stay up for the stars. But I’ve finally learned to sleep in, and have cultivated the art of napping (if possible) when the mental fog rolls in.

LS: Who are your top three favorite contemporary photographers and describe their work using one word for each.

SB:

Chris Jordan, confrontational.

Isa Leshko, empathetic.

Sebastian Salgado, important.

Violette, pot-bellied pig. Age 12. Photographer: Isa Leshko.

LS: What are some of the things that influence you/your work and your aesthetic?

SB: Though I rarely photo birds, it’s my concern for wildlife that inspired learning the botany and biology of the habitats in which creatures can thrive. My photographs aren’t flashy, but simply an attempt to “explain” this wildness, or even small wild fragments of our altered landscapes, along with the rivers and streams that sustain them.

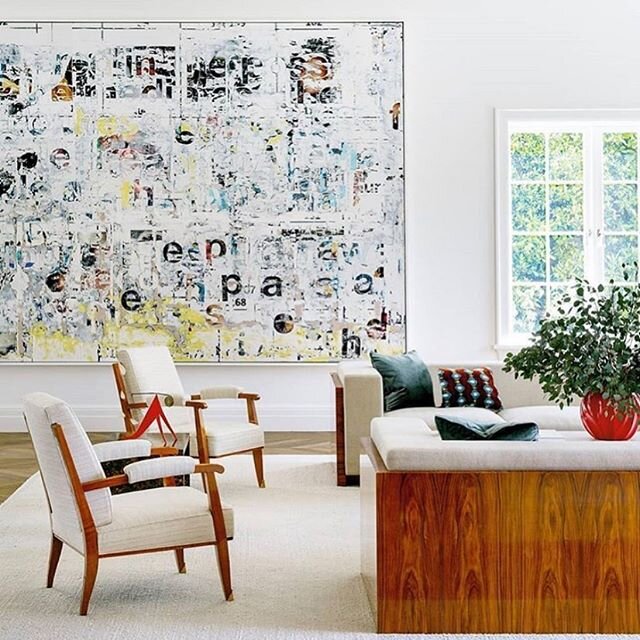

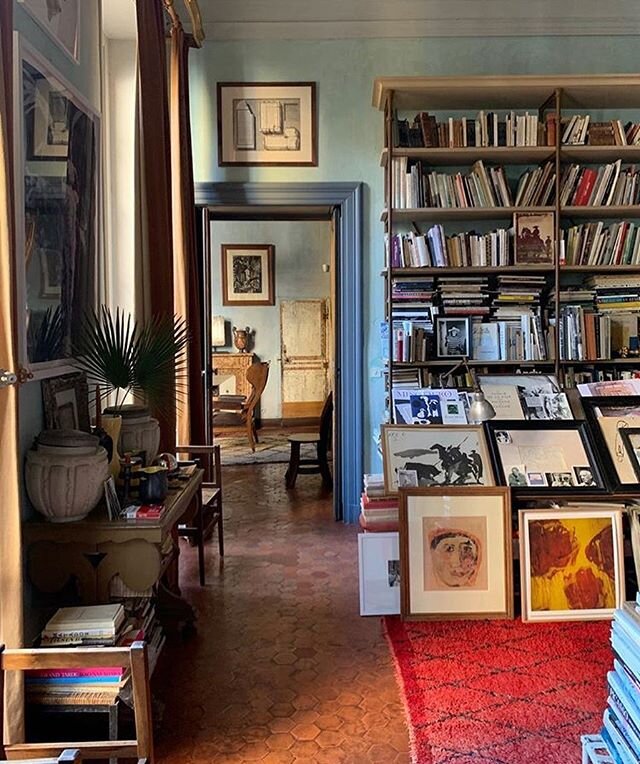

LS: What is your favorite room in the house and what surprises would we find there?

SB: Well, there will be no photographs of my house, as it is tiny and contains much more than it should. But the living room’s nearly-always-open-door looks into my little native plant garden, which hosts the towhee that chirps me awake in the morning, and the bushtits pinging away in the coffee-berry. Oh, my exciting life, but I this is where I get restored, so the lack of surprises is just fine with me.

LS: If you could take a long, meandering drive with one famous person, living or dead, who would it be? And where would you go?

SB: Someone I would make up who would be a cross between Springsteen and Thoreau and we would time travel to small towns across America and I would photo the befores and the nows.

*Lily Spindle's SHAPERS profiles the people whom we consider to be remarkable movers and shakers, doers and dreamers, trailblazers and big thinkers, the people who are doing things a little bit differently and unconventionally, with immense heart, passion, and authenticity in what they do. Artists, designers, writers, philanthropists, iconoclasts, artisans, heroines, voyagers, and all kinds of extraordinary extraordinaires will be interviewed in our SHAPERS series.